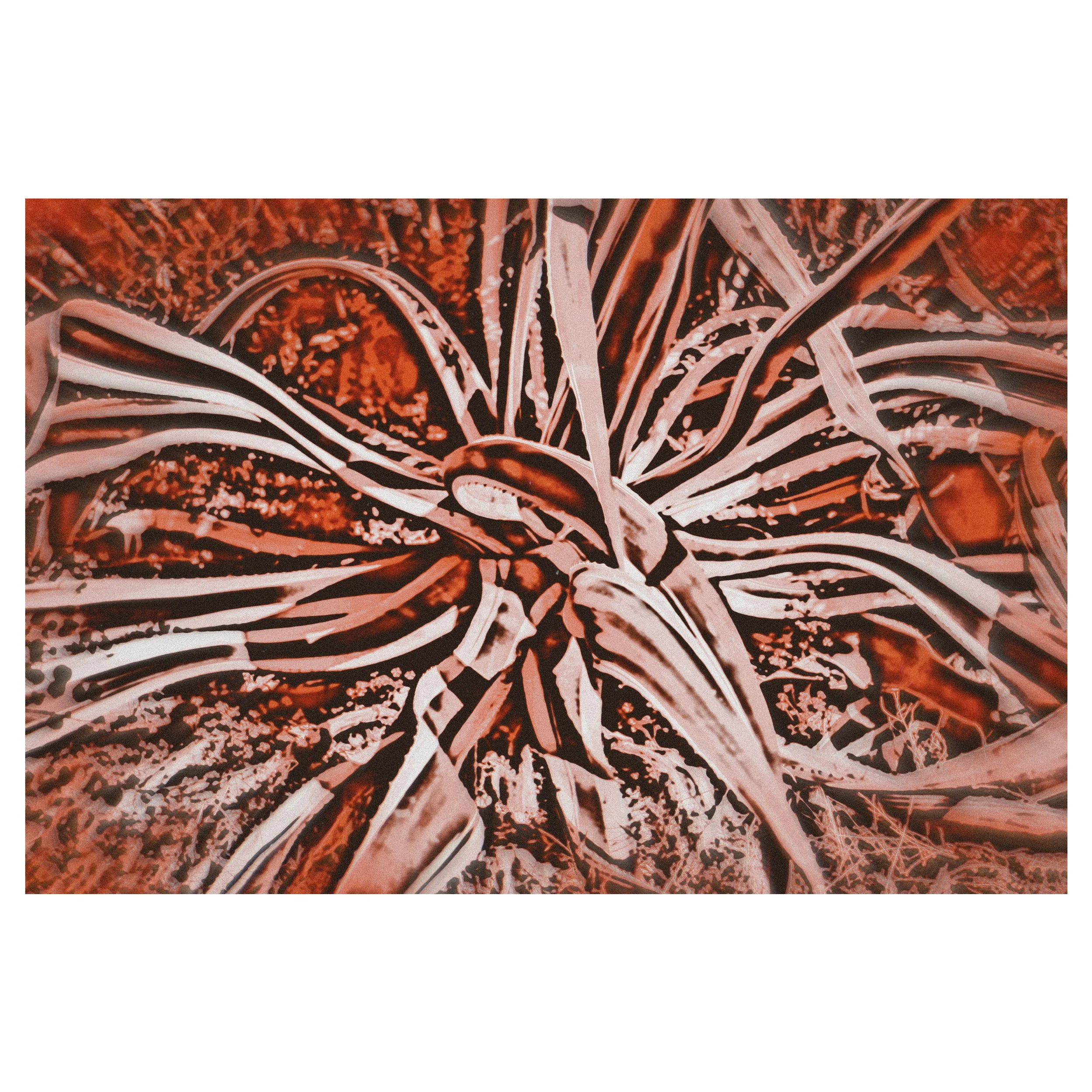

The Quiet Power of Abstract Photography in Contemporary Interiors

In a visual world increasingly dominated by immediacy, literal meaning, and constant stimulation, abstract photography occupies a quieter, more demanding space. It does not explain itself. It does not ask to be understood immediately. And for this very reason, it has become one of the most powerful visual languages in contemporary and luxury interiors.

In a visual world increasingly dominated by immediacy, literal meaning, and constant stimulation, abstract photography occupies a quieter, more demanding space. It does not explain itself. It does not ask to be understood immediately. And for this very reason, it has become one of the most powerful visual languages in contemporary and luxury interiors. Abstract photography is not a trend, nor a decorative shortcut. It is a form of visual thinking. When placed within an interior space, it does not simply “fill a wall” but alters the way that space is perceived, lived in, and remembered.

Beyond Representation: Why Abstract Works

Unlike figurative photography, abstract imagery does not anchor the viewer to a specific subject, location, or narrative. There is no place to recognize, no face to interpret, no event to decode. What remains is form, rhythm, tension, balance, and absence. This openness is precisely what makes abstract photography so compatible with contemporary interiors. Modern living spaces are no longer designed merely to host objects; they are environments meant to support moods, identities, and states of mind. Abstract photography functions as a visual pause, allowing inhabitants to project their own emotions rather than consume someone else’s story. In luxury interiors especially, abstraction introduces restraint. It avoids the obvious. It refuses spectacle. And in doing so, it communicates confidence.

Abstraction as a Spatial Tool

Abstract photography interacts with space differently than representational imagery. It does not compete with furniture, architecture, or materials. Instead, it resonates with them. Lines echo architectural structures. Colors converse with surfaces. Empty areas create breathing room in environments often overloaded with design statements. In this sense, abstract photography becomes a spatial tool, not an accessory. It can enlarge a room perceptually, soften rigid geometries, or introduce tension where everything feels too resolved. Interior designers often return to abstract works precisely because of this versatility: one image can live differently in different contexts without losing coherence.

Emotional Neutrality and Emotional Depth

One of the great misunderstandings about abstract photography is that it is “cold” or emotionally detached. In reality, abstraction removes specific emotion in order to make room for personal emotion. A figurative image tells you what to feel. An abstract image asks how you feel. This is particularly relevant in private spaces such as bedrooms, studies, and living rooms. Few people want to wake up facing a stranger’s face or a narrative they did not choose. Abstract photography offers intimacy without intrusion. Presence without imposition.

The Luxury of Time

Abstract photography also demands time. It does not deliver instant gratification. Its meaning unfolds slowly, through repeated encounters. In luxury environments—where quality is defined not by excess but by longevity—this temporal dimension matters. A work that reveals itself over years, rather than minutes, aligns with a mature idea of luxury: one based on experience, not novelty. This is why abstract photographic prints often age better than highly specific images. They do not become dated because they are not tied to a moment, a place, or a visual trend.

Materiality Matters

In abstract photography, the choice of print material is not secondary. Paper texture, surface reflection, tonal depth, and scale all contribute to the final experience. Fine art papers enhance subtle transitions and micro-contrasts. Matte surfaces reduce distraction and invite proximity. Large formats allow the viewer to enter the image physically rather than observe it from a distance. When abstraction meets high-quality printing, the photograph becomes less an image and more an object—something that occupies space with intention.

Abstract Photography as Identity

Choosing abstract photography for an interior is not a neutral act. It is a declaration of openness, curiosity, and self-awareness. It signals a willingness to live with ambiguity. To accept that not everything needs to be explained. To value atmosphere over instruction. In this sense, abstract photography does not decorate a space; it defines it. In contemporary interiors, especially those aspiring to timelessness rather than trendiness, abstract photography offers something rare: silence with depth. It does not shout. It does not persuade. It remains. And in remaining, it transforms the space around it—quietly, continuously, and profoundly.

The Human Process Behind a Photograph — Why Selling Prints Is Also a Human Act

In a time when images are consumed at the speed of a swipe, it is easy to forget that every photograph, before becoming a product, before becoming content, before becoming a print on a wall, is first and foremost the result of a human process. Not a mechanical one, not an algorithmic one, but a sequence of choices, doubts, intuitions, references, and emotional states that no machine can fully replicate.

In a time when images are consumed at the speed of a swipe, it is easy to forget that every photograph, before becoming a product, before becoming content, before becoming a print on a wall, is first and foremost the result of a human process. Not a mechanical one, not an algorithmic one, but a sequence of choices, doubts, intuitions, references, and emotional states that no machine can fully replicate. Even when photography becomes a professional activity, even when it enters the market and becomes something that is bought and sold, it does not stop being human. It simply becomes human in a more complex way.

When people think about selling photographic prints, they often imagine only the final step: the framed image, the clean mockup, the elegant interior, the product page with a price tag. What remains invisible is everything that happens before that moment. Observation comes first, long before the camera is even taken out of the bag. Observation is not only about looking at the world, but about recognizing when something resonates, when a scene, a light, a shape, or a coincidence speaks a language that feels meaningful. This is not technical skill. This is sensitivity, and sensitivity is never neutral. It is shaped by personal history, culture, music, literature, cinema, and by all the silent experiences that form who we are.

Then comes the crossover between disciplines. Photography does not exist in isolation. A photograph can be influenced by painting, architecture, graphic design, poetry, or even by the rhythm of a song. Very often, what makes an image strong is not the subject itself, but the invisible dialogue it has with other forms of expression. This is why two photographers can stand in front of the same subject and produce radically different images. They are not only photographing what they see. They are photographing what they know, what they remember, and what they feel.

Only after this inner and cultural process does the act of shooting take place. The click is not the beginning. It is the consequence. And even here, the idea that photography is only about capturing reality is misleading. Framing, timing, perspective, distortion, abstraction, and deliberate ambiguity are all tools used to interpret reality, not to reproduce it. Photography is not a mirror. It is a language. And like every language, it involves intention.

Post-production is another phase that is often misunderstood. For some, editing is seen as manipulation, as if purity existed somewhere in the raw file. In truth, post-production is a continuation of the creative process. It is where the photographer decides what the image wants to become. Contrast, color balance, texture, cropping, and tonal choices are not cosmetic details. They are narrative decisions. They define the emotional tone of the photograph and guide the viewer’s reading of the image.

And then, finally, comes the print. The most underestimated phase of all. Printing is not simply transferring an image from a screen to paper. It is a craft that requires knowledge of materials, surfaces, inks, and long-term durability. A photograph printed on matte fine art paper speaks differently than the same image printed on glossy photo paper or on textured cotton rag. The choice of paper is not neutral. It affects depth, softness, contrast, and even how the light interacts with the image in a room. This is why a print is not just a reproduction. It is a physical interpretation of a photograph.

But the human process does not end with production. It continues with context. Where will this print live? In what kind of space? With what kind of light? Surrounded by which objects, colors, and textures? A photograph designed to live in a domestic environment cannot ignore the idea of coexistence. It must dialogue with architecture and daily life. This is one of the reasons why not every good photograph is suitable as wall art. Some images work powerfully on screens, in books, or in exhibitions, but would feel intrusive or disconnected in a living room or bedroom. Choosing what becomes a print is therefore also an ethical and aesthetic responsibility.

Behind all of this, there is also the emotional dimension of offering one’s work to others. Selling a print is not only a commercial act. It is an act of exposure. It means saying: this image represents me enough that I am willing to let it enter someone else’s private space. This is not trivial. It requires confidence, but also vulnerability. Every sale is also a form of trust exchanged between two people who may never meet, but who are connected by an image.

In the age of social media, this human process becomes even more fragile. Platforms tend to reduce photography to performance metrics: likes, shares, saves, comments, reach. But none of these numbers measure what really matters in an artistic practice. They do not measure whether an image stayed in someone’s mind. They do not measure whether a photograph changed the way someone looked at a familiar place. They do not measure whether an image became part of someone’s daily visual environment and quietly influenced their mood over time.

Moreover, social interaction itself can be ambiguous and sometimes painful. A comment that disappears, a conversation that stops abruptly, a connection that vanishes without explanation. These micro-events may seem insignificant, but they touch something deeper: the desire to be seen and understood not only as a content creator, but as a person. When photography is also your voice, every interaction feels personal, even when it probably should not. This is part of the emotional cost of choosing to communicate through images.

Yet, despite this fragility, continuing to believe in the value of the process is essential. Photography, when treated seriously, is not about producing endless content. It is about constructing meaning over time. It is about coherence, research, and patience. It is about accepting that not every image will be immediately understood, and that not every audience is the right audience. Sometimes growth does not come from pleasing more people, but from finding the people who resonate with what you are truly trying to say.

This is why identity becomes central. A photographer who knows what kind of images they want to create, what kind of spaces they want their work to inhabit, and what kind of dialogue they want to establish with the viewer is already doing much more than chasing visibility. They are building a visual language. And language takes time to be learned, both by the author and by the audience.

In this sense, selling prints is not the final goal, but a natural extension of a broader creative journey. It is not about turning art into merchandise. It is about allowing images to complete their path, from inner intuition to physical presence in the world. A photograph that remains only on a hard drive or on a feed is still incomplete. The print gives it weight, duration, and a different kind of intimacy.

Ultimately, what is not seen is often what matters most. The doubts before pressing the shutter, the references that shaped the vision, the hours spent refining an image, the tests with different papers, the reflections about where and how that image will live. All of this remains invisible to the final viewer, but it is embedded in the object they hang on their wall. Every print carries a silent story of decisions and intentions.

Recognizing this does not make photography elitist. It makes it honest. It reminds us that even in a market context, creative work remains deeply human. And perhaps this is what gives value to a photograph: not only what it shows, but everything that had to happen for it to exist.

Why We Photograph: Between Control and Surrender

Photography is often described as a way to capture reality, but perhaps it would be more honest to say that photography is an attempt to negotiate with reality. Between what we want to see and what the world is willing to give us, there is a fragile space, and it is in that space that photography happens. We choose the lens, the framing, the moment, and yet something always escapes us. Light changes, people move, weather shifts, and meaning transforms. In this constant tension between intention and accident, between control and surrender, photography finds its most authentic voice.

Photography is often described as a way to capture reality, but perhaps it would be more honest to say that photography is an attempt to negotiate with reality. Between what we want to see and what the world is willing to give us, there is a fragile space, and it is in that space that photography happens. We choose the lens, the framing, the moment, and yet something always escapes us. Light changes, people move, weather shifts, and meaning transforms. In this constant tension between intention and accident, between control and surrender, photography finds its most authentic voice.

From a technical point of view, photography is built on control. We control exposure, focus, composition, color, depth of field and perspective. We study rules, we learn a grammar, we refine technique. All of this is necessary, but it is not sufficient. No matter how precise our preparation is, the world does not follow our plans. Even in a studio, with artificial lights and fixed subjects, something unpredictable always enters the frame: a reflection, a gesture, a shadow, a hesitation. Outside, in streets, landscapes and human encounters, control becomes even more fragile, and perhaps that is exactly the point. As Henri Cartier-Bresson famously said, photography is an immediate reaction, and that immediacy means that the photograph is born in a fraction of a second that never fully belongs to us.

At some point, every photographer learns that the image does not belong entirely to them. You can wait, you can search, you can prepare, but when the moment arrives you must accept what is there, not what you imagined. This is where surrender begins. Surrender is not weakness, it is attention. It is the ability to recognize that reality has its own rhythm, its own intentions, its own mysteries. When we surrender, we stop forcing meaning onto the scene and we start listening instead. Often, what we receive is richer, more complex and more alive than what we had planned. In this sense, photography becomes less about taking and more about receiving, less about conquering and more about encountering.

We all know the difference between a technically perfect image and an image that feels alive. The first can impress, the second can move. That difference does not come from resolution, sharpness or equipment. It comes from the presence of something that cannot be fully controlled: emotion, tension, silence, contradiction. An image feels alive when it carries a trace of uncertainty, when it suggests more than it explains, when it leaves space for the viewer to enter. Roland Barthes called this the punctum, the detail that wounds, that disturbs, that breaks the surface of the image. You cannot plan a punctum, you can only be open to it.

Too often we think of photography as an act of capture, as if we were taking something away from the world. But capture implies possession, and photography in its deepest form is not about possession, it is about dialogue. A dialogue between the inner world and the outer world, between memory and presence, between intention and chance. When that dialogue is absent, the image may still be correct, but it will rarely be meaningful. Meaning is not imposed, it emerges, and it emerges precisely in the space where we accept that we are not fully in charge.

When photography becomes a physical object, a print, a book, an exhibition, the question of control becomes even more complex. A print freezes an instant and gives it weight, duration and material presence. It says that this moment deserves to stay. But even then, interpretation remains open. The same image will live differently in different homes, under different lights and within different personal histories. Once the photograph leaves the author’s hands, it becomes part of someone else’s story, and this too requires surrender. Perhaps this is why choosing which images deserve to become prints is such a delicate act. Not every photograph wants to be permanent, not every image is meant to inhabit walls and rooms. Some images belong to the flow, others ask to stay. Learning to listen to that difference is part of the photographer’s responsibility.

There is a dangerous myth in photography that mastery comes from eliminating uncertainty. In reality, mastery often comes from learning how to stay present inside uncertainty. Technique gives us tools, but vulnerability gives us access. It takes courage to accept that we do not always know what we are looking for and that sometimes we discover it only after we have pressed the shutter. In this sense, photography is not only a visual practice, it is also an emotional and philosophical one. It teaches patience, humility and attention, and perhaps more than anything else, it teaches us to tolerate not knowing.

So why do we keep photographing if we cannot fully control the outcome? Because in that fragile balance between control and surrender, something true can appear. Because photography allows us to meet the world halfway, not as masters and not as passive observers, but as participants. Because every photograph is, in its own way, a small act of trust: trust that what is happening matters, trust that this fraction of time is worth remembering, trust that meaning can arise even when we do not fully understand it. In the end, photography may not be about freezing life. It may be about learning how to be present while life moves, and accepting, again and again, that some of the most beautiful images are not the ones we planned, but the ones we were humble enough to receive.

Photography Does Not Exist. There Are Many Photographies

Saying that photography does not exist may sound provocative.

In reality, it is an attempt to clarify a long-standing misunderstanding that has accompanied this medium since its origins: the idea that photography is a single, homogeneous territory governed by universal rules.

Saying that photography does not exist may sound provocative.

In reality, it is an attempt to clarify a long-standing misunderstanding that has accompanied this medium since its origins: the idea that photography is a single, homogeneous territory governed by universal rules.

Photography is, instead, a collection of different languages, each with its own purposes, responsibilities, and grammars. Speaking of photography in the singular is convenient in everyday language, but deeply misleading from a cultural standpoint.

Just as there is no single form of writing — only novels, essays, poetry, journalism — and no single cinema — only documentary, fiction, experimental film — in the same way photography does not exist as a singular entity. What exists are multiple photographies.

One Word, Too Many Meanings

Etymologically, photography means “writing with light.”

It is an elegant and poetic definition, but an incomplete one. Writing with light does not explain how, why, for whom, or according to which rules.

We use the same word to describe a wedding photograph, a medical X-ray, an advertising image, a war reportage, or a conceptual artwork shown in a gallery. These practices have little in common beyond the tool itself.

The real problem arises when we assume that all photographs should be judged by the same criteria. That is where confusion begins.

Photographic Genres as Languages

Each photographic genre is a system of shared conventions, shaped by a specific function.

Reportage photography exists to bear witness. Its grammar values clarity, narrative coherence, and contextual integrity. Excessive aestheticization or staged ambiguity can undermine its purpose.

Advertising photography, on the other hand, exists to persuade. Manipulation is not an ethical issue here, but a legitimate tool. Light, composition, color, and post-production are all carefully controlled.

Fashion photography operates within the realm of imagination and aspiration. Artifice is not concealed — it is openly embraced.

Conceptual photography allows itself ambiguity, opacity, and complexity. It does not need to explain; it needs to question.

Judging all these practices by the same standards means failing to understand the language itself.

The Fallacy of Aesthetic Judgment

One of the most evident side effects of social media is the flattening of critical judgment. Everything is reduced to I like it or I don’t like it, regardless of intention or context.

Saying “I don’t like” a documentary photograph because it is uncomfortable is like criticizing a medical report for lacking elegance.

Likewise, expecting documentary truth from conceptual photography is a misunderstanding.

The right question is not Is it beautiful?

But rather: Does it work according to its purpose?

Photography and Responsibility

This distinction is not merely theoretical — it is ethical.

In reportage and photojournalism, the decision of what to include and exclude from the frame can radically alter the meaning of a story. Photography becomes a position, not a neutral act.

In other contexts — still life, artistic, or conceptual photography — responsibility shifts from reality to conceptual coherence.

Confusing these levels leads to misplaced accusations or, conversely, to superficiality where rigor is required.

The Myth of Objectivity

Photography is often perceived as an objective record of reality. In truth, every photograph is a choice: of time, space, point of view, and language.

There is no innocent photograph.

Even the simplest image is shaped by intention, whether conscious or not.

What differentiates genres is not the presence or absence of intention, but how it is controlled, declared, or amplified.

When Photography Begins to Make Sense

Many photographers go through a phase of confusion, searching for the photography, the style, the definition. But it is often only when one accepts that photography is not a single entity that a meaningful direction emerges.

Choosing a language also means excluding others.

And exclusion is not a limitation — it is a stance.

Understanding which photography one is practicing — and which one is not — is an act of maturity.

Photography does not exist as a monolithic entity.

What exists are different photographies, often incompatible with one another, yet all legitimate when coherent with their intent.

Accepting this plurality means abandoning absolute definitions and working with greater awareness.

It means looking at images with less naivety.

And above all, it means photographing while knowing why you are doing it.

Everything else can remain outside the frame.

Can Fine Art Photography Take a Pause?

We live in a time that does not tolerate emptiness. Any unoccupied space is perceived as a lack, any silence as a mistake, any pause as a weakness. In the world of communication — and particularly in the world of photography — absence is often read as disinterest, inactivity, loss of relevance. If you don’t post, you don’t exist. If you don’t show, you are disappearing. If you stop, someone else will overtake you. But is this really true? And above all: does this constant race for attention benefit fine art photography? Does it nurture artistic research, vision, depth?

Attention, Silence, and Time in Artistic Research

We live in a time that does not tolerate emptiness. Any unoccupied space is perceived as a lack, any silence as a mistake, any pause as a weakness. In the world of communication — and particularly in the world of photography — absence is often read as disinterest, inactivity, loss of relevance. If you don’t post, you don’t exist. If you don’t show, you are disappearing. If you stop, someone else will overtake you. But is this really true? And above all: does this constant race for attention benefit fine art photography? Does it nurture artistic research, vision, depth?

Fine art photography, by its very nature, belongs to a different time. It is not always immediate, it is not necessarily reactive, and it does not inherently respond to the urgency of the present moment. It is made of observation, sedimentation, returns, second thoughts. It is made of moments in which, on the surface, nothing seems to happen, yet everything is quietly preparing itself. And still, today more than ever, fine art photography is immersed in an ecosystem that rewards visible continuity, constant presence, uninterrupted production of content. An ecosystem that often confuses the creative act with the communicative act, and that tends to measure the value of a work through the frequency of its appearance.

The question therefore becomes unavoidable: can fine art photography afford to take a pause? Or, to put it more honestly, can it afford not to be constantly visible?

For many, the answer seems obvious. No, it cannot. We live in the age of attention, and attention is a scarce resource. If you don’t cultivate it daily, you lose it. If you don’t feed the algorithm, the algorithm forgets you. If you don’t continuously offer something to the flow, the flow expels you. This reasoning has become so pervasive that it feels like a natural law, something inevitable. Yet it is a relatively recent cultural construction, not an absolute truth. It works very well for certain fields — marketing, entertainment, commercial communication — but becomes problematic when applied indiscriminately to artistic research.

Because art, and fine art photography in particular, is not born to occupy space, but to create meaning. It is not born to be seen immediately, but to be seen in the right way. It is not born to provide answers, but to raise questions. And questions need time to mature. They need silence. They need pauses.

There is a substantial difference between being present and being constantly exposed. Presence is a conscious choice; constant exposure is often a reaction. The first implies intention, the second fear. Fear of being forgotten, of losing ground, of no longer counting if one stops speaking for a moment. If left unexamined, this fear risks becoming the true engine of creative work. And when fear drives research, depth rarely survives.

Fine art photography should not arise from the need for attention, but from an inner necessity. From something that demands form, not an audience. From an urgency that does not coincide with the urgency of the feed. When research is instead bent to the rhythms of visibility, something subtle yet dangerous happens: the work stops questioning and starts pleasing. Not always in an obvious or vulgar way. Often in a refined, almost imperceptible one. Photographs are made while already thinking about how they will be received, where they will be published, what reaction they will provoke. Photography is no longer solely an act of exploration; it becomes — sometimes primarily — a strategic act.

This is not a call to demonize communication or social media. That would be naïve and detached from reality. Communication has always been part of an artist’s work, albeit in different forms. But there is a profound difference between using communication as an extension of one’s work and using one’s work as fuel for communication. In the first case, research guides presence; in the second, presence guides research. Over time, this inversion impoverishes both the work and the gaze behind it.

In this context, a pause is not a romantic retreat or an escape from the world. It is not the heroic gesture of withdrawing from the system in the name of purity. It is something far more simple and far more radical: a space of recalibration. A time in which the artist stops producing in order to be seen and returns to looking in order to understand. A time in which images do not necessarily have to go out, but are allowed to remain. To be revisited, questioned, rearranged, discarded. A time in which attention shifts from the outside to the inside.

In these moments of apparent inactivity, the most important work often happens. It is there that directions become clearer, recurring obsessions emerge, and one begins to understand what is worth pursuing and what is merely noise. It is there that photography stops being an automatic response and becomes a choice again. Yet none of this is measurable, visible, or shareable in real time. And for this reason, within the logic of continuous attention, it does not count.

And yet, if we look at the history of photography and art more broadly, the works that endure are rarely born from incessant, anxious production. They emerge from long, uneven paths, marked by accelerations and slowdowns, fertile periods and phases of apparent stillness. They are created by artists who knew how to step aside, at least partially, from the tyranny of immediacy. Not out of disdain for the public, but out of respect for the work itself.

There is also a more human, less theoretical aspect that deserves attention. The continuous pursuit of attention is exhausting. It requires constant emotional availability, perpetual mental alertness, and a readiness to expose oneself that leaves little room for fragility. Over time, this wears down not only the artist, but also the relationship with the work. Photography risks becoming a duty, a performance, a response to an external demand rather than an internal necessity. And when this happens, the gaze itself hardens.

Taking a pause, then, is not an act of weakness, but of care. Care for one’s gaze, one’s time, one’s relationship with images. It is a way of remembering that the value of a photograph does not depend on the speed with which it is shown, but on the depth with which it has been thought. That not everything needs to be said immediately, not everything needs to be seen now, not everything must be consumed the moment it is created.

Of course, a pause is not total absence, nor absolute isolation. It is modulation. A conscious slowing down. It is the ability to choose when to speak and when to remain silent, when to show and when to withhold. It is the refusal of automatism. In this sense, the pause becomes an integral part of research, not its negation. It becomes an active time, even if invisible.

Perhaps the most honest question is not whether fine art photography can take a pause, but whether it can afford not to. Whether it can truly grow, deepen, and mature while remaining constantly under the spotlight. Whether it can continue to question the world without granting itself the time to question itself. The answer is not the same for everyone, nor should it be. Every path is different, every balance personal. But ignoring the question altogether means passively accepting a logic that is not neutral, and that often works against the complexity of artistic work.

In an era that constantly demands presence, choosing, at times, to stop is a countercultural gesture. Not to disappear, but to return with greater awareness. Not to withdraw from the gaze of others, but to rediscover one’s own. Fine art photography, after all, is not only a matter of images produced, but of a gaze cultivated. And the gaze, like any living thing, needs room to breathe.

Perhaps the real challenge today is not to keep attention perpetually high, but to learn not to confuse attention with value.

Black and White Photography: A Language, Not a Shortcut

Black and white photography has always carried a particular weight. It feels serious, timeless, cultured. It evokes history, authorship, intention. Perhaps for this reason, it is often perceived as a shortcut to depth: remove color, add gravitas. And yet, this perception is both true and dangerously misleading.

Black and white photography has always carried a particular weight. It feels serious, timeless, cultured. It evokes history, authorship, intention. Perhaps for this reason, it is often perceived as a shortcut to depth: remove color, add gravitas. And yet, this perception is both true and dangerously misleading.

Used with awareness, black and white is one of the most powerful visual languages available to photography. Used without it, it risks becoming a cosmetic gesture — a way to elevate images that struggle to stand on their own in color. The question, then, is not whether black and white is “better” than color, but why we choose it. And what kind of black and white we are actually using.

At its best, black and white is not subtraction but transformation. It does not merely remove color; it reorganizes vision. It asks the photographer to think in terms of light rather than hue, structure rather than surface, rhythm rather than decoration. When color disappears, relationships become visible: between forms, between tones, between presences in space. There is no chromatic distraction to rely on. Everything must hold together through composition, contrast, and intention.

This is why black and white demands more, not less. It is unforgiving. Weak light becomes flat. Poor composition becomes obvious. Hesitant framing loses its alibi. When the image works, it does so because the photographer has embraced the discipline of seeing differently, not because something has been hidden.

And yet, in contemporary practice, black and white is often used precisely as a hiding place. Many images are converted to monochrome not because the photographer saw the scene in black and white, but because color exposed its limitations. Unbalanced palettes, unpleasant hues, visual noise — all softened by the elegance of grayscale. In these cases, black and white becomes a form of visual makeup: tasteful, flattering, but ultimately superficial.

This is not a moral failure, but it is an aesthetic one. The problem is not experimentation, but confusion between language and effect. A true black and white photograph is conceived as such from the beginning. It is not a rescue operation performed in post-production. It is a way of seeing before it is a way of editing.

Historically, black and white was not a choice but a condition. Early photographers worked within technical constraints, yet produced images of extraordinary depth and complexity. What we admire in their work is not the absence of color, but the mastery of light. Shadows were not mistakes to be corrected but elements to be shaped. Highlights were not accidents but decisions. The image was built through tonal architecture, not chromatic seduction.

When color photography became dominant, black and white did not disappear. Instead, it transformed from necessity into statement. Choosing black and white became a declaration: this image is not about realism, but about interpretation. It is not about how things look, but how they mean.

In this sense, black and white is profoundly dialectical. It creates tension between presence and absence, between what is shown and what is withheld. Color tells us what something is; black and white asks us to consider why it is there at all. It slows the gaze. It resists consumption. It invites contemplation rather than recognition.

This is why many photographers turn to black and white during moments of introspection or transition. It can function as a refuge — a quieter space, a reduction of stimuli, a way to regain control over vision. There is nothing wrong with this. But refuge should not become avoidance. When black and white is used to escape complexity rather than confront it, its power dissolves.

A meaningful black and white image does not feel “artistic” by default. It feels necessary. Color would not add information; it would dilute it. The photograph exists in monochrome because that is the only form in which it makes sense. Anything else would be excess.

This is the difference between style and language. Style is repeatable, comforting, often marketable. Language is demanding, specific, and sometimes uncomfortable. Style asks to be liked; language asks to be understood.

In today’s visual culture, where images are produced and consumed at an overwhelming speed, black and white often benefits from an aura of seriousness. It slows the viewer down, or at least signals that slowing down is expected. This makes it appealing as a branding tool, a way to position work as “artistic” or “thoughtful.” But when this aura is not supported by substance, it collapses quickly.

The most compelling black and white photographs are those in which the photographer has accepted the risk of exposure. Nothing is hidden. The image either holds, or it doesn’t. Light is not decoration; it is structure. Contrast is not drama; it is meaning. Absence is not emptiness; it is intention.

So the real question is not whether black and white is a powerful choice. It unquestionably is. The question is: how is it being used? As a refuge or as a dialogue? As a filter or as a language? As an aesthetic mask or as a form of thought?

Every photographer who works in black and white eventually reveals their position through their images. Some seek elegance, others silence, others control. Some seek depth, others safety. None of these motivations are inherently wrong. But they are not equivalent.

Black and white photography does not make an image profound. It exposes whether depth was there to begin with.

And so the question remains, open and necessary:

what kind of black and white do you use?

WHEN IMAGES STOP TRYING TO IMPRESS

We live in an age saturated with images. Photography has never been so accessible, so immediate, so omnipresent. Screens accompany us from the moment we wake up to the moment we fall asleep, and images flow continuously through our days: social feeds, advertisements, news, entertainment. In this context, photography is increasingly asked to perform.

On subtraction, space and the value of quiet photography

We live in an age saturated with images. Photography has never been so accessible, so immediate, so omnipresent. Screens accompany us from the moment we wake up to the moment we fall asleep, and images flow continuously through our days: social feeds, advertisements, news, entertainment. In this context, photography is increasingly asked to perform. It must attract attention quickly, stand out instantly, explain itself without hesitation. The image is expected to be loud, assertive, unmistakable.

Yet this constant demand for visibility comes at a cost. The more images try to impress, the faster they are consumed. What captures attention for a second often disappears the next. Visual impact replaces visual endurance. Photography becomes an object of momentary stimulation rather than a lasting presence.

This is not a critique driven by nostalgia, nor a rejection of contemporary visual culture. It is simply an observation of how abundance alters perception. When everything competes for attention, attention itself becomes fragile. And photography, which once required time and distance, is now compressed into an instant reaction.

In this landscape, silence appears almost countercultural.

Many contemporary photographs are constructed to deliver their message immediately. They rely on strong contrasts, explicit narratives, striking subjects. There is little left unresolved. Everything is designed to be understood at first glance. This approach works well in fast-moving digital environments, but it often reveals its limits when photography leaves the screen and enters physical space.

An image that performs well online does not necessarily perform well on a wall. What feels exciting in a feed can become overwhelming in a room. When a photograph insists on being noticed, it risks exhausting the gaze over time. Instead of opening a space, it closes it.

This is where the question of subtraction becomes central.

Subtraction is often misunderstood as minimalism for its own sake, or as a lack of content. In reality, subtraction is an act of precision. It is a way of deciding what truly matters within the frame and allowing everything else to fall away. By removing what is unnecessary, the image gains clarity. By gaining clarity, it gains space. And space allows the image to breathe.

A quiet photograph does not demand attention. It does not try to convince. It does not explain itself exhaustively. It exists with a certain restraint, leaving room for the viewer to enter. This does not make it weaker; on the contrary, it gives it endurance. Images that do not shout can stay longer. They resist the fatigue of constant exposure.

This approach becomes especially relevant when photography is conceived as something that lives in a space rather than passing through it. A photograph displayed in a home, a studio or a public interior is not encountered once. It is seen repeatedly, often indirectly, sometimes without conscious focus. It becomes part of the environment, part of daily life.

In this context, photography shifts from being a statement to being a presence.

Images that coexist with architecture, light and silence require a different sensibility. They cannot rely on shock or excess. They must hold their ground quietly. They must be able to remain without overwhelming. This is why subtraction is not an aesthetic choice alone, but an ethical one. It respects both the space and the viewer.

My work moves in this direction deliberately. Not as a reaction against contemporary photography, but as a positioning within it. I am interested in images that do not compete with their surroundings, but enter into dialogue with them. Photographs that can inhabit a room rather than dominate it.

This choice affects every stage of the process: composition, colour, scale, printing. It also affects how images are presented and released. Instead of offering collections as complete sets, I introduce photographs individually. One image at a time. This is not a marketing strategy, but a conceptual one. Each photograph deserves its own space, its own time to be encountered.

Attention, today, is one of the rarest resources. Treating it with care becomes part of the work.

Quiet photography is not about emptiness. It is about density without excess. It is about images that reveal themselves gradually, that change slightly depending on light, distance and mood. Images that do not exhaust their meaning immediately, but unfold over time.

Some photographs are made to be seen once. Others are made to be lived with.

In choosing silence, subtraction and space, photography regains a certain dignity. Not as an object of consumption, but as a companion. Not as a spectacle, but as a presence that remains.

The Role of Authorial Photography in Shaping Interior Spaces

In contemporary interior design, visual choices are no longer secondary considerations. Spaces today are conceived as cultural environments—places that communicate identity, sensibility, and intention. Within this landscape, authorial fine art photography has assumed a central role, offering more than visual appeal: it introduces thought, authorship, and narrative into the built environment.

In contemporary interior design, visual choices are no longer secondary considerations. Spaces today are conceived as cultural environments—places that communicate identity, sensibility, and intention. Within this landscape, authorial fine art photography has assumed a central role, offering more than visual appeal: it introduces thought, authorship, and narrative into the built environment.

Unlike decorative imagery produced for immediate consumption, fine art photography carries the weight of a personal vision. It is the result of sustained research, formal exploration, and a conscious relationship with reality. To place such a work within an interior is to invite a point of view—one that unfolds slowly and rewards attentive looking.

Beyond decoration: photography as presence

Many interiors rely on imagery as a purely decorative device. These images often function as visual fillers, chosen for their neutrality or trend alignment. Their purpose is to complete a wall, not to activate a dialogue.

Authorial photography operates differently. Each photograph exists as an autonomous work, capable of sustaining meaning beyond its immediate context. When introduced into an interior space, it does not dissolve into the background; instead, it establishes a quiet but deliberate presence.

This presence alters the perception of the space itself. Walls are no longer surfaces to be adorned, but sites of visual and conceptual exchange.

Constructing spatial identity through images

Every interior tells a story, whether intentionally or not. The selection of visual elements—particularly photographic works—plays a decisive role in shaping that narrative.

Fine art photography contributes to spatial identity by:

Introducing a coherent visual language

Reinforcing the conceptual character of an environment

Communicating cultural awareness and authorship

In private interiors, such works often become intimate companions, images that resonate with personal memory and lived experience. In professional or public settings, they function as curatorial statements, signalling precision, depth, and aesthetic commitment.

Photography in public, professional, and transitional spaces

Increasingly, architects, interior designers, and curators integrate fine art photography into offices, hospitality spaces, galleries, and commercial environments. This is not a decorative trend, but a curatorial strategy.

In these contexts, photography operates as a mediator between architecture and human experience. It softens, complicates, and enriches the spatial narrative. A carefully chosen photographic work can slow down perception, introduce rhythm, and create moments of reflection within otherwise functional environments.

Rather than serving as branding imagery, authorial photography lends credibility and depth, allowing spaces to communicate values without explicit statements.

Time, endurance, and visual depth

One of the defining qualities of fine art photography is its relationship with time. Unlike images designed for rapid consumption, authorial works are meant to endure. Their meaning does not exhaust itself at first glance; instead, it unfolds gradually.

This temporal dimension makes fine art photography particularly suited to interiors conceived as long-term spaces. Such images age with the environment, acquiring new associations and emotional resonances as time passes.

Living with photography: a curatorial choice

To live or work with fine art photography is to make a curatorial decision. It implies an engagement with artistic research and an openness to visual complexity.

When photography enters daily life through interior spaces, it transcends institutional boundaries. Art becomes part of routine experience—quiet, persistent, and profoundly human.

Conclusion

Integrating authorial photography into interior spaces is not an act of embellishment, but one of definition. It reflects a desire to inhabit environments shaped by intention, depth, and visual intelligence.

Fine art photography does not simply decorate space—it articulates it. Through carefully produced works, interiors gain character, continuity, and a sense of presence that extends beyond design trends.

In contemporary spatial practice, photography is no longer an accessory. It is a curatorial element, capable of shaping how spaces are perceived, remembered, and lived.

“Leaving the Provincial Mindset: The World Is Bigger Than Your Hometown”

There is a particular illusion that many people are raised with: the idea that the world begins and ends where we are born. A town, a region, a cultural habitus becomes the centre of everything — and somehow the measure of what is valuable. Yet nothing could be more limiting. The truth is brutally simple: the world is far wider, richer, and more diverse than the comfortable little corners we come from.

Leaving the Provincial Mindset: The World Is Bigger Than Your Hometown

There is a particular illusion that many people are raised with: the idea that the world begins and ends where we are born. A town, a region, a cultural habitus becomes the centre of everything — and somehow the measure of what is valuable. Yet nothing could be more limiting. The truth is brutally simple: the world is far wider, richer, and more diverse than the comfortable little corners we come from.

In photography, in art, and in culture in general, provincial thinking creates invisible borders long before geography does. It tells you which style is legitimate and which isn’t. It tells you what “sells” and what doesn’t. It also tells you that recognition must come from local approval — as if the value of your work needed to be validated by the neighbours.

But creativity, by nature, refuses borders. The moment you publish your work online, you don’t belong to a village anymore. You belong to a world.

What provincialism really is

Provincialism is not a matter of geography. There are provincial minds in huge cities and cosmopolitan minds in tiny villages. It is a mindset, not a location. A provincial mind believes that what happens “here” is more real than what happens elsewhere. It believes local judgment is universal truth.

A global mind knows the opposite: what we see locally is only a fragment — and often the least relevant one.

Why the digital world exposes provincialism

For decades, artists had to rely on local recognition. Today, the audience is global by default. You post a photograph and in a matter of seconds it can be seen in Tokyo, New York, Reykjavík or Singapore.

And yet, surprisingly, many still behave as if they were speaking only inside a small room. They shape their language, their topics, even their ambitions based on the expectations of people who live just a few kilometres from them.

The digital age didn’t make us global. It simply exposed who was already thinking globally and who wasn’t.

Nothing truly meaningful happens “locally” anymore

Art, culture, technology, and even taste circulate at global speed. Local validation is often the slowest and most conservative one. The same communities that hesitate today are the ones that will praise you tomorrow — when someone else (usually abroad) has confirmed your worth first.

The irony? Many of the greatest Italian artists became celebrated abroad long before Italy even noticed.

If your audience is abroad, speak their language

We live in a multilingual planet. English is a tool, not a betrayal of identity. It’s not a rejection of origins — it’s an expansion of them. When your audience is international, writing in English is not an affectation. It’s communication. It’s intelligence. It’s professionalism.

Why restrict your voice to a provincial frequency when the world speaks another language?

Where you live is not where you belong

Creative identity isn’t tied to the street you were born in. If your work resonates more in Japan, or Canada, or Australia, that’s not accidental — it’s a signal. A photograph doesn’t know geography. Beauty doesn’t need a passport.

You don’t need permission from your hometown to exist. The world already exists for you.

The world is bigger — and so are you

You can stay attached to local habits, but you’re free to move mentally and artistically anywhere you want. That’s the privilege of our time. We are the first generation that can belong everywhere.

A provincial mindset will always feel threatened by a global one. But that’s not your problem. Your job is to open windows, not close them.

Some people are born to stay local.

Others are born to cross borders — even without moving.

The world is bigger than your hometown.

And so is your work.

You don't have to belong to a place to be legitimate.

One of the greatest Italian illusions is to believe that one's career must “pass through” a certain territory: the city, the province, the association, the group, the gallery of reference. As if a local baptism were necessary in order to exist elsewhere.

It is exactly the opposite. The most interesting works are created when one frees oneself from the need to belong. When you abandon the idea that someone has to “validate” what you do. Art has no accent. Photography does not speak dialect. It is not Roman, Milanese, Apulian or Lombard. It is not even Italian, French or Japanese. It is a universal language, understandable on every continent. Images do not ask which province you live in: they only ask what you have to say.

Provincialism arises when we are more concerned with being recognised close to home than communicating with the rest of the world. The world is looking for what Italy still ignores

It is paradoxical: outside Italy, there is enormous interest in Italian photography, in Mediterranean poetics, in our light, our cultural sensitivity. But many Italian photographers, instead of engaging with that world, chase local approval. Meanwhile: the most active buyers are foreign, international platforms generate more opportunities, and the most dynamic markets are outside Italy.

It is cruel but simple: what goes unnoticed in the provinces can become valuable in other countries. You don't have to apologise for looking further afield. There is still a strange idea that leaving your local context is tantamount to betraying it. But it is not a moral choice: it is a professional choice. It is seriousness, vision, future. The only real betrayal would be to stay where there are no opportunities. The world is bigger than your home.

This statement is deliberately provocative, but it is also profoundly true. Remaining closed off to local dynamics means giving up on the world at a time in history when the world is more open, closer and more accessible than ever before.

Provincialism is a form of self-limitation. Breaking out of it is a duty to oneself. Looking far ahead is not presumption, it is survival. The future of photography — as with any creative discipline — will not be decided by a city, a province or a single local group. It will be decided by those who know how to connect with the world, engage with different cultures, build international networks, share and grow.

We don't have to ask anyone's permission to do this.

We just need to have the courage to look up.

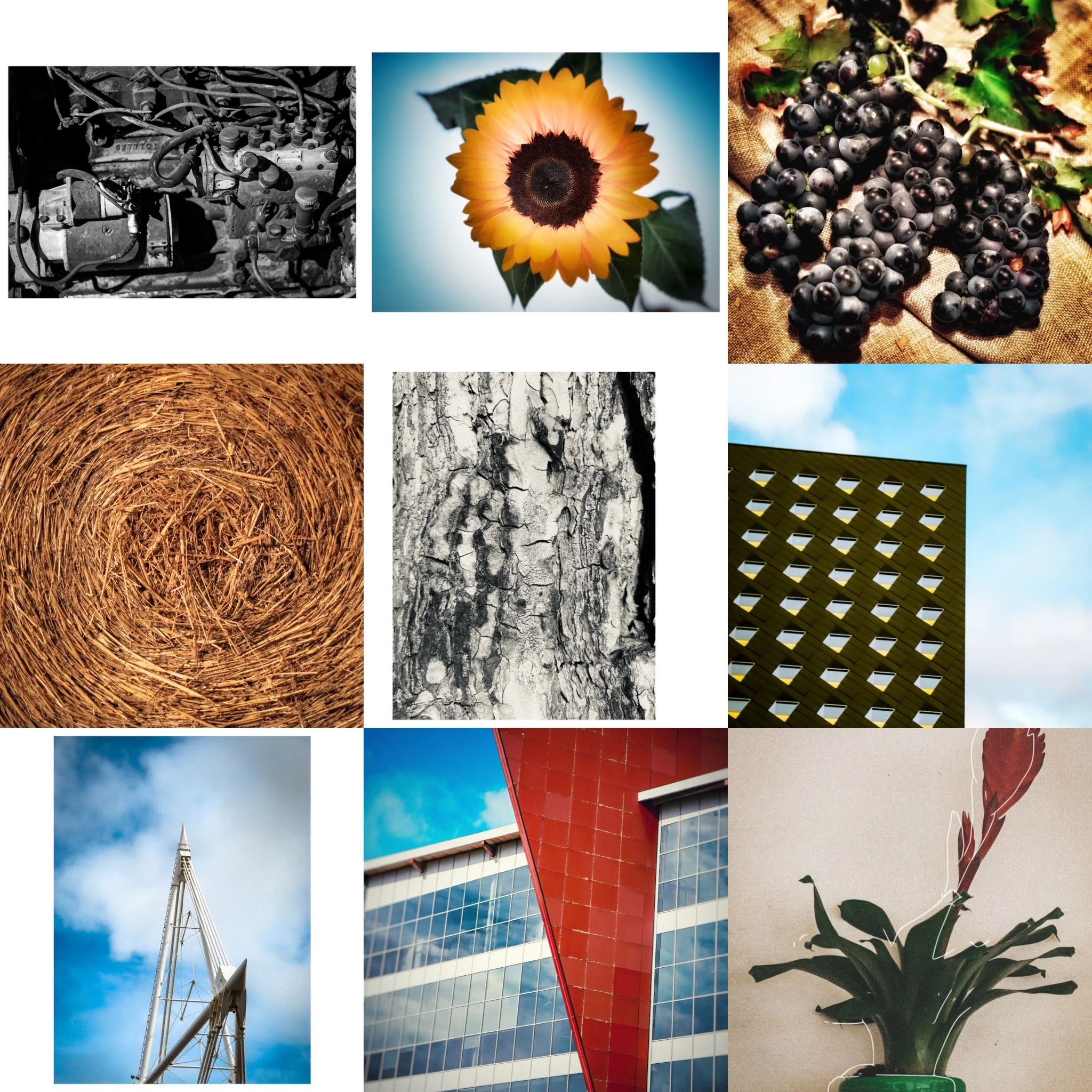

The Silent Role of Color: Emotional Architecture in Contemporary Photography

Color is often treated as a detail—an accessory, an aesthetic choice, a stylistic preference. But within contemporary photography, color has become something far more profound: a silent architect of emotional experience. It shapes the viewer’s perception long before the subject or composition is consciously processed. It structures mood, amplifies intention, and governs how an image is remembered.

Color is often treated as a detail—an accessory, an aesthetic choice, a stylistic preference. But within contemporary photography, color has become something far more profound: a silent architect of emotional experience. It shapes the viewer’s perception long before the subject or composition is consciously processed. It structures mood, amplifies intention, and governs how an image is remembered.

We tend to speak of composition, narrative, and technical choices, but color works in a different dimension: it communicates without argument, without explanation, without noise. It simply enters the viewer and rearranges the emotional space inside them.

Today, in a world oversaturated with visuals, where attention is constantly fragmented, color is no longer a superficial attribute. It is a language. It is a story. It is a psychological tool capable of transforming even the simplest subject into a moment of deep resonance.

Color as an Emotional Blueprint

Every photograph has an emotional blueprint—an invisible structure guiding the viewer’s reaction. Color is often the foundation of this structure, even before composition begins to speak.

Warm tones pull the viewer inward, creating intimacy and a sense of human presence. Cool tones push them outward, invoking distance, silence, or contemplation. Neutral palettes can introduce stillness, humility, or timelessness. Saturated tones inject urgency, while desaturated ones convey memory, nostalgia, or an almost cinematic melancholy.

In contemporary photography, color has become less about representing reality and more about constructing reality. It moves the image into the territory of emotional design, a place where the photographer is no longer simply documenting, but orchestrating.

The emotional architecture of an image is not accidental. It is the result of how light interacts with tone, how hue guides attention, how shadows compress or release tension. Color becomes the silent “atmosphere builder”—the element that decides whether a scene feels overwhelming, serene, nostalgic, or enigmatic.

Beyond Aesthetics: Color as Concept

Aesthetic choices are only the surface. In contemporary practice, color has become conceptual. It is no longer just “beautiful”; it carries meaning.

A monochromatic palette, for example, can strip a scene of distractions and push the viewer toward form, gesture, or rhythm. A bold color contrast can introduce conflict. A muted landscape can reveal emotional fatigue. A vibrant urban scene can celebrate the chaos of modernity while hinting at our inability to fully digest it.

Color is not decoration—it is interpretation.

In architectural photography, cool metal tones can become metaphors for anonymity or ambition. In travel photography, warm light can transform distant places into emotional states rather than destinations. In portraiture, a deliberate palette can reveal psychological truths that the subject’s expression alone cannot carry.

Contemporary photographers increasingly use color to embed metaphors directly into the image. It becomes a carrier of themes such as isolation, exuberance, memory, identity, or dissonance. And in doing so, it shifts the photograph from representation to conversation.

The Psychology of Color: A Dialogue with the Viewer

The emotional power of color is rooted in psychology. Our brains process color faster than they process shape. We feel color before we understand it.

This is why:

Red triggers alertness, desire, or urgency.

Blue calms, distances, or intellectualizes.

Yellow awakens attention and evokes warmth or fragility.

Green evokes balance, natural rhythm, or renewal.

Orange and teal, a modern cinematic pairing, create tension between warmth (life) and coolness (distance).

Black and white remove color entirely—but in doing so, amplify structure, silence, and emotional clarity.

These reactions are not fixed, but intertwined with cultural memory, personal experience, and visual literacy. What matters is that color becomes a dialogue: the photographer speaks, the viewer responds—sometimes consciously, often without realizing it.

Color and Memory: How Images Linger

Every photographer knows that some images stay with the viewer long after they’re seen. Color is one of the reasons why.

A vivid palette can brand an image into memory with immediacy, like a neon sign. A soft, dusty palette might enter more quietly but linger longer, like a scent. A monochrome palette can transform a contemporary moment into something that feels mythic or timeless.

Color shapes not only how we perceive the moment, but how we remember it. A city photographed in cold blue tones becomes a place of solitude. The same city photographed in warm amber becomes nostalgic. Nothing has changed except the emotional key.

This emotional manipulation is not deceitful—on the contrary, it is intentional. It reveals that photography is never objective. It is always an act of emotional construction.

Color Grading as a Narrative Tool

In the digital era, color grading has expanded the palette of possibilities. Editing is no longer a correction—it is an authorship gesture.

Contemporary photographers are increasingly defined by their chromatic signature: a distinct palette that carries their emotional world across projects and subjects. Whether subtle or bold, this signature becomes a form of narrative consistency.

Color grading can:

unify a series,

create mood,

sculpt atmosphere,

guide storytelling,

and articulate the photographer’s voice.

Color grading is not cheating; it is writing. It is the final paragraph of the story the image wants to tell.

The Future of Color in Photography

Looking ahead, color will continue to evolve from decorative attribute to intellectual structure. As AI expands visual culture and images multiply without pause, color becomes a way for photographers to reclaim intentionality.

In a landscape of algorithm-generated visuals, human-created color choices stand out precisely because they are emotional, imperfect, and deeply personal.

Color is not simply what we see—it is what we feel.

In contemporary photography, color is not the finishing touch.

It is the architecture of emotion itself.

Why Photographers Feel the Need to Write About Other Photographers

There’s an old misconception in the photography world: the idea that talking about other photographers means “giving away visibility” or even helping the competition. It’s a limiting mindset, unable to capture the true nature of art: a continuous dialogue.

(A reflection on contemporary photography, artistic growth, and creative coexistence)

There’s an old misconception in the photography world: the idea that talking about other photographers means “giving away visibility” or even helping the competition. It’s a limiting mindset, unable to capture the true nature of art: a continuous dialogue.

The reality is simple: photographers don’t live in isolation. They exist inside a wide, diverse landscape filled with influences, stories and perspectives.

Speaking about other artists doesn’t diminish your space — it expands it.

Photography as an ecosystem, not an arena

The photography and art market is enormous. There is no single audience, no single style, no single way of seeing.

Talking about other photographers doesn’t mean stepping aside: it means positioning yourself within a living, dynamic ecosystem.

Coexistence is smarter than competition.

The most effective way to stay relevant today is not to hide, not to build walls, not to fight imaginary battles.

It is to offer your own art as an original contribution inside a shared landscape.

Discussing other artists enriches your audience

People who follow photography blogs don’t want only images. They want to understand how a photographer thinks, what inspires them, which references shape their vision.

When an artist talks about another artist, they:

show visual literacy,

enrich the reader,

educate the eye,

position themselves as a thoughtful, competent guide.

And when a photographer demonstrates cultural awareness, their perceived value increases.

Knowing others helps you understand yourself

Every photographer is the sum of the visions they have absorbed.

Studying the work of others doesn’t mean imitation — it means discovering where you stand, what you want to say, and how you can evolve from shared inspirations.

Exploring other artists allows you to:

expand your visual vocabulary,

identify what sets you apart,

develop your artistic voice.

You don’t become unique by isolating yourself. You become unique by absorbing, transforming, and transcending.

Cultural depth = authority

Google rewards content that demonstrates expertise, structure and depth.

Writing about other photographers allows you to include context, references and analysis — all elements that build trust, for both algorithms and human readers.

A blog that looks outward, not only inward, becomes far more authoritative.

Conclusion

The world of photography is too vast and inspiring to be approached as a battlefield.

The most intelligent way to inhabit it is through coexistence, dialogue, and shared culture.

Talking about other photographers does not reduce your space.

It increases the value of everyone, including yourself.

Reflections of a Contemporary Photographer: Between Creative Freedom and Sustainability

There comes a moment in every artist’s life when one must look in the mirror and ask: “Why do I do what I do?”

It’s a simple, yet terrifying question. Because in today’s world, creating is never only a poetic act — it’s also an economic one. Every photograph, every work of art, exists between two extremes: freedom and necessity. Between what comes from within, and what must survive outside.

There comes a moment in every artist’s life when one must look in the mirror and ask: “Why do I do what I do?”

It’s a simple, yet terrifying question. Because in today’s world, creating is never only a poetic act — it’s also an economic one. Every photograph, every work of art, exists between two extremes: freedom and necessity. Between what comes from within, and what must survive outside.

My reflection on this topic is born from everyday experience, not theory.

Every time I publish a new work, upload an image, or someone asks, “How much does it cost?”, I realize that the line between art and market is not a wall — it’s a fluid territory full of nuances.

And within those nuances often lies the fate of the artist.

Art as Language, the Market as Ecosystem

For those who work in contemporary or conceptual photography, the question is clear:

How can we preserve artistic integrity without falling victim to commercial logic?

The answer lies in how we understand the market.

The art market is not just a machine that buys and sells images. It’s an ecosystem of meanings, relationships, and symbols — the environment where ideas become visible, where the audience meets the author, and where the value of an artwork finds its place in the world.

To see the market as an enemy is a mistake.

The market is simply the economic translation of a human need — the need to share.

Every collector, buyer, and viewer seeks a connection with the artist.

They buy a photograph not merely because it’s beautiful, but because it speaks to them.

When art and market coexist with balance, they empower one another.

The Photographer as Author and Craftsman

Being a photographer today means living between two worlds — the world of ideas and the world of matter.

A conceptual photographer builds images that are born from thought. But to make them real, they must also face production, materials, formats, communication, and sales.

To be a fine art photographer today is to be an entrepreneur of your own vision.

It’s not about selling out, but about knowing how to present yourself.

An artist who refuses contact with the market risks becoming invisible — and an invisible artist, no matter how brilliant, leaves no trace.

Every photograph is a bridge between what we want to say and those willing to listen.

The market is simply the road that allows that bridge to stand.

The Fear of “Selling”

In many artistic environments, the word selling still sounds like blasphemy.

Why?

Because selling means exposure. It means accepting that your work will be judged, chosen, or rejected. It means stepping out of the temple of intimacy into the real world.

And yet, all great masters had a relationship with patrons or markets — from Caravaggio to Mapplethorpe, from Weston to Cindy Sherman.

Selling does not pollute art; intention does.

Creating to sell is one thing. Selling what you created with honesty is another — and, for me, the only authentic path.

The Value of a Photograph

In fine art photography, value is never just technical.

It’s not defined by cameras or lenses, but by thought, composition, and light as language.

However, in the art market, value also takes form through rarity, edition, printing quality, authenticity, and presentation.

A collector doesn’t buy a photo — they buy a fragment of vision. A way of seeing the world.

That’s why every artist must be aware of how they present their work: titles, texts, editions, formats, materials — everything communicates. Everything contributes to perceived value.

Professionalism does not kill art; it sustains it.

Freedom and Sustainability

Creative freedom is the heart of art, but even freedom needs roots.

You cannot create if you’re always suspended between dream and survival.

To be a sustainable artist means treating your career as a long-term project: planning, investing in education, building a coherent online presence, and maintaining dialogue with curators, galleries, and collectors.

Art only truly lives when it’s shared.

Every photographer should ask not only what do I want to say, but also to whom, and how can I make it reach them.

The Role of Digital Platforms

We live in a time when the border between art and communication is increasingly thin. Instagram, LinkedIn, Behance, blogs — all are potential spaces for art. The difference is no longer in the medium, but in the message.

A contemporary photographer must use digital platforms not as passive showcases but as places of dialogue.

Posting a photo is not enough; one must contextualize it, tell its story, explain why it exists.

Digital hasn’t killed art — it has expanded it.

It’s up to us to decide whether to walk that path with authenticity or haste.

The Risk of Standardization

The greatest danger today is not commodification, but homogenization. When everything is visible, everything risks looking the same.

A photographer who wants to stand out must dare to be different. Being out of fashion can be a form of freedom.

Trends fade — vision endures.

Conceptual photography still has much to say in a world of shouted images.

Creating to move is human. Creating to please is a trap.

Art as Dialogue

Art is never a monologue; it’s a dialogue between creator and observer.

The market amplifies that dialogue — giving it visibility, tools, and context.

Even the most intimate work needs to be seen to be complete.

The true value of a photograph doesn’t lie in its price, but in its impact — in the moment someone stops, looks, and feels something.

That’s when art wins.

The Fragile Balance

There is no exact point where art ends and the market begins.

There is only a fluid space where the artist learns to move with integrity and balance.

To create is to communicate. To communicate is to expose yourself. And to expose yourself means, inevitably, to enter the market.

The difference lies in the honesty with which you walk that path.

An artist must be both a dreamer and a builder.

To create with freedom, but also to give structure to that freedom.

Only then does art stop floating in the void — and find its place in the world.

Because ultimately, every image is an encounter between the one who creates and the one who, looking at it, recognizes themselves.

The photographic composition: the invisible order that gives meaning to the gaze

There are images that remain, and images that disappear the moment after we see them. The difference is almost never the subject itself. It is what sustains it. It is the invisible structure that makes it necessary, inevitable, alive.

When I photograph, I realise that composition comes even before the visible content: it is the secret grammar through which the world takes form — the space where an image stops being “something to look at” and becomes “something that speaks”.

There are images that remain, and images that disappear the moment after we see them. The difference is almost never the subject itself. It is what sustains it. It is the invisible structure that makes it necessary, inevitable, alive.

When I photograph, I realise that composition comes even before the visible content: it is the secret grammar through which the world takes form — the space where an image stops being “something to look at” and becomes “something that speaks”.

Many people think of composition as a set of rules, a kind of operational system to be applied to make images “more beautiful”. Others treat it as a cage, from which they try to emancipate themselves in the name of the famous “I break the rules”, often obtaining nothing more than a confused or fragile picture.

For me it is the opposite. Composition is not ornament, not decoration, and certainly not a prison. It is the founding act of photography. Before I press the shutter, the photograph already exists — in the gaze. It lives in the act of framing, of choosing, of defining what remains and what is excluded. That is the moment in which the voice of the image is born.

Every time I frame, I perform a gesture that is both mental and perceptive: I delimit a field, I set a threshold, I decide which relationships have the right to exist and which will disappear. The camera is only the terminal medium. Real photography happens earlier — and it happens in the eye. It is worth repeating, in a world obsessed with megapixels: never confuse the pen with the text.

Choice as origin

An image is never the mere recording of what was in front of me. It is what I chose to retain. And equally, what I chose to leave outside.

The photographic act is not additive — it is subtractive. It is an act of distillation: from a world that is complex, ambiguous, and overflowing with stimuli, I extract a precise balance. A tiny but irreversible decision: here yes, here no.

When a collector encounters an image and perceives it as “complete”, what they recognise is not the subject, but the invisible order that sustains it. They sense that nothing is accidental, and that every element is necessary. That inevitability is the true hallmark of authorship — what makes an image unrepeatable. Nothing is truly “by chance”: it is the manifestation of an inner design shaped by memory, by experience, by knowledge and sensitivity.

Before the gaze, there is order

We live as if vision were natural, spontaneous, neutral. It is not. Our perceptual system constantly organises the chaos of the visible world into structures we can understand. Even someone who never picks up a camera is already “composing”, unconsciously: the mind selects, emphasises, reduces, connects.

Photography simply brings this hidden process into awareness.

To compose is to take responsibility for a gesture that the mind already performs at a primordial level. When I look, I am already shaping reality into relations; when I photograph, I give that gesture a definitive form.

The frame as a field of forces

A photographic frame is never just a rectangle: it is a field of tension. Every element inside it has weight, direction, gravity, pull.

Composition is the art of orchestrating these forces.

When I place a line in the frame, I am not “filling a space”, I am directing a movement through the viewer’s perception. When I leave a wide margin, I am not leaving emptiness — I am creating breath. When I bring a subject toward the edge, I am not merely repositioning it — I am placing it in a state of visual risk, a delicate vibration.

The images that endure are the ones in which this field of forces can be felt, even when not consciously recognised. The viewer may not know how to explain it technically — but the body understands it long before the intellect intervenes. Composition always acts before thought.

Visual sensing and recognition

Before we register what a picture shows, we feel how it holds itself: order or disorder, stability or tension, attraction or escape.

The psychology of form — from Gestalt theory to contemporary neuro-aesthetics — confirms that we do not see “objects”, we see relationships.

Meaning is not in the things, but between them.

A photograph that succeeds does not merely display: it discloses. It does not illustrate: it reveals structure. And structure is never neutral.

Composition is not a geometric exercise — it is an emotional orientation of space.

This is why I believe composition is not something that is added to the world, but the very thing that makes the world readable. It is the bridge between phenomenon and meaning. The hidden scaffolding that prevents the visible from collapsing into noise.

The decisive moment (before the click)