The Human Process Behind a Photograph — Why Selling Prints Is Also a Human Act

In a time when images are consumed at the speed of a swipe, it is easy to forget that every photograph, before becoming a product, before becoming content, before becoming a print on a wall, is first and foremost the result of a human process. Not a mechanical one, not an algorithmic one, but a sequence of choices, doubts, intuitions, references, and emotional states that no machine can fully replicate. Even when photography becomes a professional activity, even when it enters the market and becomes something that is bought and sold, it does not stop being human. It simply becomes human in a more complex way.

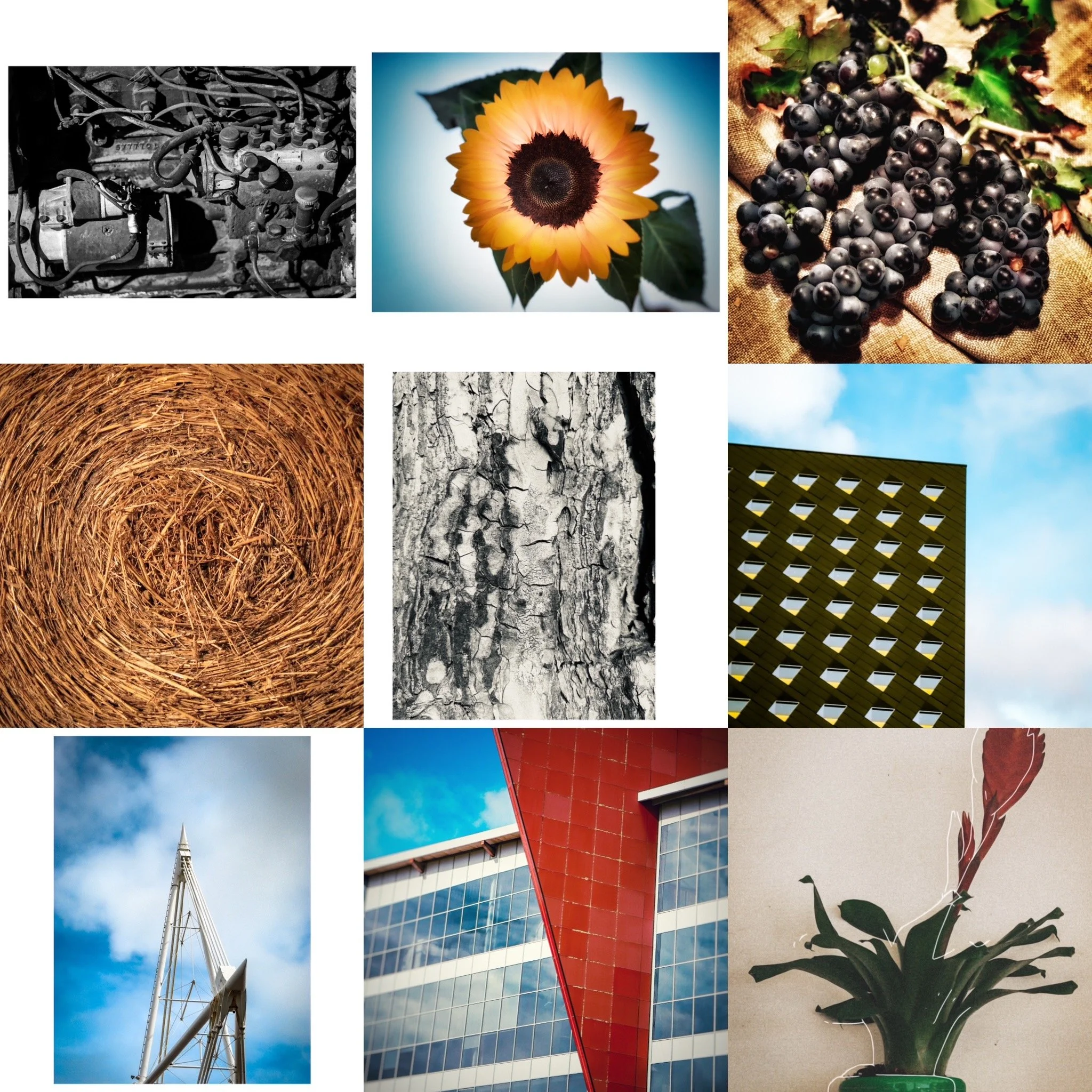

When people think about selling photographic prints, they often imagine only the final step: the framed image, the clean mockup, the elegant interior, the product page with a price tag. What remains invisible is everything that happens before that moment. Observation comes first, long before the camera is even taken out of the bag. Observation is not only about looking at the world, but about recognizing when something resonates, when a scene, a light, a shape, or a coincidence speaks a language that feels meaningful. This is not technical skill. This is sensitivity, and sensitivity is never neutral. It is shaped by personal history, culture, music, literature, cinema, and by all the silent experiences that form who we are.

Then comes the crossover between disciplines. Photography does not exist in isolation. A photograph can be influenced by painting, architecture, graphic design, poetry, or even by the rhythm of a song. Very often, what makes an image strong is not the subject itself, but the invisible dialogue it has with other forms of expression. This is why two photographers can stand in front of the same subject and produce radically different images. They are not only photographing what they see. They are photographing what they know, what they remember, and what they feel.

Only after this inner and cultural process does the act of shooting take place. The click is not the beginning. It is the consequence. And even here, the idea that photography is only about capturing reality is misleading. Framing, timing, perspective, distortion, abstraction, and deliberate ambiguity are all tools used to interpret reality, not to reproduce it. Photography is not a mirror. It is a language. And like every language, it involves intention.

Post-production is another phase that is often misunderstood. For some, editing is seen as manipulation, as if purity existed somewhere in the raw file. In truth, post-production is a continuation of the creative process. It is where the photographer decides what the image wants to become. Contrast, color balance, texture, cropping, and tonal choices are not cosmetic details. They are narrative decisions. They define the emotional tone of the photograph and guide the viewer’s reading of the image.

And then, finally, comes the print. The most underestimated phase of all. Printing is not simply transferring an image from a screen to paper. It is a craft that requires knowledge of materials, surfaces, inks, and long-term durability. A photograph printed on matte fine art paper speaks differently than the same image printed on glossy photo paper or on textured cotton rag. The choice of paper is not neutral. It affects depth, softness, contrast, and even how the light interacts with the image in a room. This is why a print is not just a reproduction. It is a physical interpretation of a photograph.

But the human process does not end with production. It continues with context. Where will this print live? In what kind of space? With what kind of light? Surrounded by which objects, colors, and textures? A photograph designed to live in a domestic environment cannot ignore the idea of coexistence. It must dialogue with architecture and daily life. This is one of the reasons why not every good photograph is suitable as wall art. Some images work powerfully on screens, in books, or in exhibitions, but would feel intrusive or disconnected in a living room or bedroom. Choosing what becomes a print is therefore also an ethical and aesthetic responsibility.

Behind all of this, there is also the emotional dimension of offering one’s work to others. Selling a print is not only a commercial act. It is an act of exposure. It means saying: this image represents me enough that I am willing to let it enter someone else’s private space. This is not trivial. It requires confidence, but also vulnerability. Every sale is also a form of trust exchanged between two people who may never meet, but who are connected by an image.

In the age of social media, this human process becomes even more fragile. Platforms tend to reduce photography to performance metrics: likes, shares, saves, comments, reach. But none of these numbers measure what really matters in an artistic practice. They do not measure whether an image stayed in someone’s mind. They do not measure whether a photograph changed the way someone looked at a familiar place. They do not measure whether an image became part of someone’s daily visual environment and quietly influenced their mood over time.

Moreover, social interaction itself can be ambiguous and sometimes painful. A comment that disappears, a conversation that stops abruptly, a connection that vanishes without explanation. These micro-events may seem insignificant, but they touch something deeper: the desire to be seen and understood not only as a content creator, but as a person. When photography is also your voice, every interaction feels personal, even when it probably should not. This is part of the emotional cost of choosing to communicate through images.

Yet, despite this fragility, continuing to believe in the value of the process is essential. Photography, when treated seriously, is not about producing endless content. It is about constructing meaning over time. It is about coherence, research, and patience. It is about accepting that not every image will be immediately understood, and that not every audience is the right audience. Sometimes growth does not come from pleasing more people, but from finding the people who resonate with what you are truly trying to say.

This is why identity becomes central. A photographer who knows what kind of images they want to create, what kind of spaces they want their work to inhabit, and what kind of dialogue they want to establish with the viewer is already doing much more than chasing visibility. They are building a visual language. And language takes time to be learned, both by the author and by the audience.

In this sense, selling prints is not the final goal, but a natural extension of a broader creative journey. It is not about turning art into merchandise. It is about allowing images to complete their path, from inner intuition to physical presence in the world. A photograph that remains only on a hard drive or on a feed is still incomplete. The print gives it weight, duration, and a different kind of intimacy.

Ultimately, what is not seen is often what matters most. The doubts before pressing the shutter, the references that shaped the vision, the hours spent refining an image, the tests with different papers, the reflections about where and how that image will live. All of this remains invisible to the final viewer, but it is embedded in the object they hang on their wall. Every print carries a silent story of decisions and intentions.

Recognizing this does not make photography elitist. It makes it honest. It reminds us that even in a market context, creative work remains deeply human. And perhaps this is what gives value to a photograph: not only what it shows, but everything that had to happen for it to exist.